"Gender Equality: Not for Women Only"

| Michael S. Kimmel, Ph. D. * Professor of Sociology State University of New York Stony Brook, New York, USA Lecture prepared for International Women's Day Seminar, European Parliament, Brussels - 8 March 2001 Men and Gender Equality – What Can Men Gain? Chairperson: Mrs Maj Britt Theorin Committee on Women’s Rights and Equal opportunities Seminar organized by the European Parliament and the Swedish Presidency Contact at the EP: Marleen Lemmens: [ mlemmens@europarl.eu.int ] |

|

It is a great pleasure to speak before you today on International Women's

Day. I am grateful to Mrs. Nicole Fontaine, President of the European

Parliament, and to Margareta Winberg, the Swedish Minister for Gender

Equality for honoring me with the invitation to speak here with you.

It is 90 years today since the first official International Women's Day

was celebrated in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland, organized by

the great German feminist Clara Zetkin, who wanted a single day to

remember the 1857 strike of garment workers in the U.S. that led to the

formation of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. On March 19,

1911 - the anniversary has changed since then - more than a million women

and men rallied to demand the right to work, to hold public office, and to

vote.

Think of how much has changed in those 90 years! Throughout most, if not

all of Europe today, women have: gained the right to vote, to own property

in their own name, to divorce, to work in every profession, to join the

military, to control their own bodies, to challenge men's presumed

"right" to sexual access once married, or on a date, or in the

workplace,

Indeed, the women's movement is one of the great success stories of the

20th century, perhaps of any century. It is the story of a monumental,

revolutionary transformation of the lives of more than half the

population. But what about the other half.?

Today, this movement for women's equality remains stymied, stalled. Women

continue to experience discrimination in the public sphere. They bump

their heads on glass ceilings in the workplace, experience harassment and

less-than fully welcoming environments in every institution the public

sphere, still must fight to control their own bodies, and to end their

victimization through rape, domestic violence, and trafficking in women.

I believe that the reason that the movement for women's equality remains

only a partial victory has to do with men. In every arena - in politics,

military, workplace, professions, and education - the single greatest

obstacle to women's equality is the behaviors and attitudes of men.

I believe that changes among men represent the next phase of the movement

for women's equality - that changes among men are vital if women are to

achieve full equality. Men must come to see that gender equality is in

their interests - as men.

This great movement for gender equality has already begun to notice that

men must be involved in the transformation. The Platform for Action

adopted at the Fourth World Congress on Women, in Beijing in 1995 said

"The advancement of women and the achievement of equality between

women and men are a matter of human rights and a condition for social

justice and should not be seen in isolation as a women's issue."

Four years later, a Fact Sheet entitled "Men and Equality" from

the Swedish Ministry of Industry, Employment and Communications, put it

this way:

"Traditionally, gender equality issues have been the concern of

women. Very few men have been involved in work to achieve equality.

However, if equality is to become a reality in all areas of society, a

genuine desire for change and active participation in the part of both

women and men are called for."

But why should men participate in the movement for gender equality? Simply

put, I believe that these changes among men will actually benefit men,

that gender equality is not a loss for men, but an enormously positive

thing that will enable us to live the kinds of lives we say we want to

live.

In order to make this case, I will begin by pointing to several arenas in

which women's have changed so drastically in the past half‑century,

and suggest some of the issues I believe we men are currently facing as a

result.

First, women made gender visible. Women have

demonstrated the centrality of gender in social life; in the past two

decades, gender has joined race and class as the three primordial axes

around which social life is organized, one of the primary building blocks

of identity.

This

is, today, so obvious that it hardly needs mentioning. Parliaments have

Gender Committees, and the Nordic

countries even have Ministers for Gender Equality. Every university in

the U.S. has a Women's Studies Program. Yet just as often we forget just

how recent this all is. The first Women's Studies program in the world was

founded in 1972.

Second, women have transformed the workplace. Women are in the workplace

to stay. Almost half the labor force is female. I often demonstrate this

point to my university classes by asking the women who intend to have

careers to raise their hands. All do. Then I ask them to keep their hands

raised if their mothers have had a career outside the home for more than

ten years without an interruption. Half put their hands down. Then I ask

them to keep their hands raised if their grandmothers had a career for ten

years. Virtually no hands remain raised. In three generations, they can

visibly see the difference in women's working lives.

Just 40 years ago, in 1960, only about 40% of European adult women of

working age were in the labor force; only Austria and Sweden had a

majority of working-age women in the labor force. By 1994, only Italy,

Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg and Spain did not have a majority of

working-age women in the labor force, and the European average had nearly

doubled.

This

has led to the third area of change in women's lives: the efforts to

balance work and family life. Once upon a time, not so long ago, women

were forced to choose between career and family. But beginning in the

1970s, women became increasingly unwilling to choose one or the other.

They wanted both. Could a woman "have it all?" was a pressing

question in the past two decades. Could she have a glamorous rewarding

career and a great loving family?

The answer, of course, was "no." Women couldn't have it all

because... men did. It's men who have the rewarding careers outside the

home and the loving family to come home to. So if women are going to have

it all, they are going to need men to share housework and childcare. Women

have begun to question the "second shift," the household shift

that has traditionally been their task, after the workplace shift is over.

Finally, women have changed the sexual landscape. As the dust is settling

from the sexual revolution, what emerges in unmistakably finer detail is

that it's been women, not men, who are our era's real sexual pioneers.

Women now feel empowered to claim sexual desire. Women can like sex, want

sex, seek sex. Women feel entitled to pleasure. They have learned to say

yes to their own desires, claiming, in the process, sexual agency.

And men? What's been happening with men while women's lives have been so

utterly and completely transformed? To put it bluntly, not very much. Sure

some men have changed in some ways, but most men have not undergone a

comparable revolution. This is, I think, the reason that so many men seem

so confused about the meaning of masculinity these days.

In a sense, of course, our lives have changed dramatically. I think back

to the world of my father's generation. Now in his mid-70s, my father

could go to an all-male college, serve in an all male military, and spend

his entire working life in a virtually all-male working environment. That

world has completely disappeared.

So our lives have changed. But what have men done to prepare for this

completely different world? Very little. What has not changed are the

ideas we have about what it means to be a man. The ideology of masculinity

has remained relatively intact for the past three generations. That's

where men are these days: our lives have changed dramatically, but the

notions we have about what it means to be a man remain locked in a pattern

set decades ago, when the world looked very different.

What is that traditional ideology of masculinity? In the mid- I 970s, an

American psychologist offered what he called the four basic rules of

masculinity:

(1) "No Sissy Stuff' - masculinity is based on the relentless

repudiation of the feminine. Masculinity is never being a sissy.

(2) "Be a Big Wheel" - we measure masculinity by the size of

your paycheck. Wealth, power, status are all markers of masculinity. As a

U.S. bumper sticker put it: "He who has the most toys when he dies,

wins."

(3) "Be a Sturdy Oak" - what makes a man a man is that he is

reliable in a crisis. And what makes him reliable in a crisis is that he

resembles an inanimate object. A rock, a pillar, a tree,

(4) "Give 'em Hell" - also exude an aura of daring and

aggression. Take risks; live life on the edge. Go for it.

The past decade has found men bumping up against the limitations of that

traditional definition, but without much of a sense of direction about

where they might go to look for alternatives. We chafe against the edges

of traditional masculinity, but seem unable or unwilling to break out of

the constraints we feel by those four rules. Thus the defensiveness, the

anger, the confusion that is everywhere in evidence.

These limits will become most visible around the four areas in which women

have changed most dramatically: making gender visible, the workplace, the

balance between work and home, and sexuality. They suggest the issues that

must be placed on the agenda for men, and a blueprint for a transformed

masculinity.

Let me pair up those four rules of manhood with the four arenas of change

in women's lives and suggest some of the issues I believe we are facing

around the world today.

First, though we now know that gender is a central axis around which

social life revolves, most men do not know they are gendered beings.

Courses on gender are still populated mostly by women. Those gender

studies books on every university press list are still read virtually

entirely by women.

I often tell a story about a conversation I observed in a feminist theory

seminar that I participated in about a decade ago. A white woman was

explaining to a black woman how their common experience of oppression

under patriarchy bound them together as sisters. All women, she explained,

had the same experience as women, she said.

The black woman demurred from quick agreement. "When you wake up in

the morning and look in the mirror," she asked the white woman,

"what do you see?"

"I

see a woman," responded the white woman hopefully.

"That's

the problem," responded the black woman. "I see a black woman.

To me race is visible, because it is how I am not privileged in society.

Because you are privileged by race, race is invisible to you. It is a

luxury, a privilege not to have to think about race every second of your

life."

I groaned, embarrassed. And, as the only man in the room, all eyes turned

to me. "When I wake up and look in the mirror," I confessed,

"I see a human being. The generic person. As a middle class white

man, I have no class, no race and no gender. I'm universally

generalizable. I am Everyman."

Lately,

I've come to think that it was on that day in 1980 that I became a middle

class white man, that these categories actually became operative to me.

The privilege of privilege is that the terms of privilege are rendered

invisible. It is a luxury not to have to think about race, or class, or

gender. Only those marginalized by some category understand how powerful

that category is when deployed against them.

Let me give you another example of how privilege is invisible to those who

have it. Many of you have email addresses, and you write email messages to

people all over the world. You've probably noticed that there is one big

difference between email addresses in the United States and email

addresses of people in other countries: your addresses have "country

codes" at the end of the address. So, for example, if you were

writing to, someone in South Africa, you'd put "za" at the end,

or "jp" for Japan, or "uk" for England (United

Kingdom) or"de" for Germany (Deutschland). But when you write to

people in the United States, the email address ends with "edu"

for an educational institution, "org" for an organization,

“gov" for a federal government office, or "com" or

"net" for commercial internet providers. But not us. Why not?

Why is it that the United States doesn't have a country code?

It is because when you are the dominant power in the world, everyone else

needs to be named. When you are "in power," you needn't draw

attention to yourself as a specific entity, but, rather, you can pretend

to be the generic, the universal, the generalizable. From the point of

view of the United States, all other countries are "other" and

thus need to be named, marked, noted. Once again, privilege is invisible.

In the world of the Internet, as Michael Jackson sang, "we are the

world."

Becoming aware of ourselves as gendered, recognizing the power of gender

as a shaping influence in our lives, is made more difficult by that first

rule of manhood - No Sissy Stuff. The constant, relentless efforts by boys

men to prove that they are "real men" and not sissies or weak or

gay is a dominant theme, especially in the lives of boys. As long as there

is no adequate mechanism for men to experience a secure, confident and

safe sense of themselves as men, we develop our own methods to "prove

it." One of the central themes I discovered in my book, Manhood in

America was the way that American manhood became a relentless test, a

constant, interminable demonstration.

My recent research into the "gendered" nature of the resurgence

of far-right neo-Nazi skinhead movements - movements of boys and

young men - has revealed that these movements are fueled by this desire to

prove masculinity by denying manhood to "others" - Jews, women,

gays, immigrants.

As a culture, we must make gender visible, and give young boys and men the

means to develop a secure, confident, inner sense of themselves as men.

Only then will we be able to breathe a sigh of relief.

The

second arena in which women's lives have changed is the workplace. Recall

the second rule of manhood: Be a Big Wheel. Most men derive their identity

as breadwinners, as family providers. Often, though, the invisibility of

masculinity makes it hard to see how gender equality will actually benefit

us as men. For example, while we speak of the "feminization of

poverty" we rarely "see" its other side - the

"masculinization of wealth." While in the U.S. women's wages are

expressed as a function of men's wages - so we read that women earn 70

cents for every man's dollar - what is concealed is what we might see if

women's wages were the norm against which men's were measured. Men, on

average, earn $1.30 for every dollar women earn. Now suddenly privilege is

visible!

On the other hand, the economic landscape has changed dramatically. And

currently, the economy has not necessarily been kind to most men either.

The great global expansion of the 1990s affected the top 20% of the labor

force. There are fewer and fewer "big wheels." European

countries have traded growth for high unemployment, which will mean that

more and more men will feel as though they haven't made the grade, will

feel damaged, injured, powerless, men who will need to demonstrate their

masculinity all over again.

Now, remember: here come women into the workplace in unprecedented

numbers. Just when men's economic breadwinner status is threatened, women

appear on the scene as easy targets for men's anger. Recently I appeared

on a television talk show opposite three "angry white males" who

felt they had been the victims of workplace discrimination. The show's

title, no doubt to entice a large potential audience was "A Black

Woman Took My Job." In my comments to these men, I invited them to

consider what the word "my" meant in that title, that they felt

that the jobs were originally "theirs," that they were entitled

to them, and that when some "other" person - black, female - got

the job, that person was really taking "their" job. But by what

right is that his job? Only by his sense of entitlement, which he now

perceives as threatened by the movement towards workplace gender equality.

It is also this context in which we must consider the question of sexual

harassment. Sexual harassment in the workplace is a distorted effort to

put women back in their place, to remind women that they are not equal to

men in the workplace, that they are, still, just women, even if they are

in the workplace. Sexual harassment is a way of maintaining that sense of

entitlement, of maintaining the illusion that the public sphere really

belongs only to men. Sexual harassment is a way to remind women that they

are not yet equals in the workplace, that they really don't belong there.

Every major corporation law firm,

and university is scrambling to implement sexual harassment policies, to

make sure that sexual harassment will be recognized and punished. This

usually consists of explaining what sexual harassment is, and, for the

men, how to avoid doing it, and, for the women, what to do if it happens

to you. But our challenge is greater than admonition and post‑hoc

counseling. Our challenge will be to prevent sexual harassment before it

happens.

And

that will require that we demonstrate to men what men will gain by

supporting women's efforts to end sexual harassment. Not only because

sexual harassment is enormously costly - as increased rates of

absenteeism, higher job turnover, retraining costs and lower productivity

are just some of the results. But if you are a manager, your job

performance depends on the strong performance of those who report to you.

You should want everyone who works for you to feel comfortable, at their

best, able to really produce. And thus it is in your interest as a man to

make sure that everyone who works for you - male and female - feels

comfortable, confident and safe in the workplace. Sexual harassment hurts

women by reducing women's productivity. But it also hurts men because it

hurts the women we work with, and therefore reduces our ability to work at

out best as well.

It

is also in our interests as men to begin to better balance work and family

life. We have a saying in the U.S. that "no man on his deathbed ever

wished he spent more time at the office."

Men will also need to balance work and family life. But remember the third

rule of manhood - "Be a Sturdy Oak. What has traditionally made men

reliable in a crisis is also what makes us unavailable emotionally to

others. We are increasingly finding that the very things that we thought

would make us real men impoverish our relationships with other men and

with our children.

Fatherhood, friendship, partnership all require emotional resources that

have been, traditionally, in short supply among men, resources such as

patience, compassion, tenderness, attention to process. A "man isn't

someone you'd want around in a crisis," wrote the actor Alan Alda,

"like raising children or growing old together."

In the United States, men become more active fathers by "helping

out" or by "pitching in" and that that they spend

"quality time" with their children. But it is not "quality

time" that will provide the deep intimate relationships that we say

we want, either with our partners or with our children. It's quantity time

- putting in those long, hard hours of thankless, unnoticed drudge work.

It's quantity time that creates the foundation of intimacy. Nurture is

doing the unheralded tasks, like holding someone when they are sick, doing

the laundry, the ironing, washing the dishes. After all, men are capable

of being surgeons and chefs, so we must be able to learn how to sew and to

cook.

Workplace and family life are also joined in the

public sphere. Several different kinds of policy reforms have been

proposed to make the workplace more "family friendly" - to make

the workplace more hospitable to our efforts to balance work and family.

These reforms generally revolve around three issues: on-site childcare,

flexible working hours, and parental leave. But how do we usually think of

these family friendly workplace reforms? We think of them as women's

issues. But these are not women's issues, they're parents' issues, and to

the extent that we, men, identify ourselves as parents, they are reforms

that we will want. Because they will enable us to live the lives we say we

want to live. We want to have our children with us; we want to be able to

arrange our work days to balance work and family with our wives and we

want to be there when our children are born.

On

this score, we American have so much to learn from Europeans, especially

from the Nordic countries, which have been so visionary in their efforts

to involve men in family life. In Sweden, for example, men are actively

encouraged by state policies to take parental leave to be part of their

children's first months. Before the institution of "Daddy Days"

less than 20% of Swedish men took any parental leave at all. Today,

though, the percentage of men who do has climbed to over 90%. That's a

government that has "family values."

Finally,

let's examine the last rule of manhood - "Give 'em Hell" - What

this says to men is to take risks, live dangerously. It means we have to

talk about sex and violence.

Remember that the greatest change in sexuality over the past 40 years has

been among women. Just at the moment women are saying "yes" to

their own sexual desires, however, there's an increased awareness of the

problem of rape all over the world, especially of date and acquaintance

rape. In one recent U.S. study, 45% of all college women said that they

had had some form of sexual contact against their will, and a full 25% had

been pressed or forced to have sexual intercourse against their will. When

one psychologist asked freshmen men over the past ten years if they would

commit rape if they were certain they could get away with it, almost

one-half said they would.

Ironically, when men speak of rape they do not speak with a voice of

power, control, domination. Listen, for a moment to a 23 year old man in

San Francisco, who was asked to think about under what circumstances he

might commit rape. He has never committed rape. He's simply an average

guy, considering the circumstances under which he would commit an act of

violence against a woman. Here's what he says:

Let's say I see a woman and she looks really pretty and really

clean and sexy and she's giving off

very feminine, sexy vibes. I think, wow I would love to make love to

her, but I know she's not interested. It's a tease. A lot of times a woman

knows that she's looking really good and she'll use that and flaunt it and

it makes me feel like she's laughing at me and I feel degraded.

If I were actually desperate enough to rape somebody it would be

from wanting that person, but also it would be a very spiteful thing, just

being able to say 'I have power over you and I can do anything I want with

you' because really I feel that they have power over me just by their

presence. Just the fact that they can come up to me and just melt me makes

me feel like a dummy, makes me want revenge. They have power over me so I

want power over them.

Notice how the stockboy also speaks not with the voice of someone in

power, of someone in control over his life, but rather with the voice of

powerlessness, of helplessness. For him, violence is a form of revenge, a

form of retaliation, of getting even, a compensation for the power that he

feels women have over him.

I think that perspective has been left out of our analyses of men's

violence - both at the interpersonal, micro level of individual acts of

men's violence against women-rape and battery, for example - and the

aggregate, social and political analysis of violence expressed at the

level of the nation state, the social movement, or the military

institution. Violence may be more about getting the power to which you

feel you're entitled than an expression of the power you already think you

have.

I believe that we must see men's violence as the result of a breakdown of

patriarchy, of entitlement thwarted. Again and again, what the research on

rape, on domestic violence finds is that men initiate violence when they

feel a loss of power to which they felt entitled. Thus he hits her when

she fails to have the dinner ready, when she refuses to meet his sexual

demands, i.e. when his power over her has broken down - not when she has

dinner ready or is willing to have sex, which are, after all, expressions

of his power and its legitimacy.

And this question of entitlement lies at the heart of current

controversies over sex trafficking all over the world. As we have tried to

confront this new international problem, we have focused on

"supply" - especially the international cartels who often kidnap

and imprison young girls and women - and, of course, extended our

compassion for the "product," the women themselves. But few, if

any, policies have targeted the "demand" side of the equation,

policies that might be aimed at the men who are the consumers of these

purloined and oppressed products., Why? Because we somehow understand that

men feel entitled to consume women's bodies, however they might be

supplied.

Nearly

20 years ago, anthropologist Peggy Reeves Sanday proposed a continuum.of

propensity to commit rape upon which all societies could be plotted - from

rape prone to rape free. (For the curious, by the way, the United States

was ranked as a highly rape prone society, far more than any country in

Europe; Norway and Sweden were among the most rape free.) Sanday found

that the single best predictors of rape-proneness were (1) whether the

woman continued to own property in her own name after marriage, a measure

of women's autonomy; and (2) father's involvement in child‑rearing,

a measure of how valued parenting is, and how valued women's work.

So clearly here is an arena in which women's economic autonomy is a good

predictor of their safety - as is men's participation in child-rearing. If

men act at home the way we say we want to act, women will be safer.

Surely, these questions of violence and sexuality are an arena where we

need strong measures to make clear our intolerance for date and

acquaintance rape, laws that protect women, social attitudes that believe

women who do come forward. And here, also, is another arena in which men's

support of feminism will enable men to live the lives we say we want to

live. If we make it clear that we, as men, will not tolerate a world in

which women do not feel safe, and if we make it clear to our individual

partners that we understand that no means no, then - and only then - can

women begin to articulate the "yes" that is also their right.

CONCLUSION

Rather

than resisting the transformation of our lives that gender equality

offers, I believe that we should embrace these changes, both because they

offer us the possibilities of social and economic equality, and because

they also offer us the possibilities of richer, fuller, and happier lives

with our friends, with our lovers, with our partners, and with our

children. We, as men, should support gender equality - both at work and at

home. Not because it's right and fair and just- although it is those

things. But because of what it will do for us, as men. At work, it means

working to end sexual harassment, supporting family friendly workplace

policies, working to end the scourge of date and acquaintance rape,

violence and abuse that terrorize women in our societies. At home it means

sharing housework and childcare, as much because our partners demand it as

because we want to spend that time with our children and because housework

is a rather conventional way of nurturing and loving.

The feminist transformation of society is a revolution-in-progress. For

nearly two centuries, we men have met insecurity by frantically shoring up

our privilege or by running away. These strategies have never brought us

the security and the peace we have sought. Perhaps now, as men, we can

stand with women and embrace the rest of this revolution - embrace it

because of our sense of justice and fairness, embrace it for our children,

our wives, our partners, and ourselves,

Ninety-three years ago, 15,00 American women marched in New York demanding

better pay, shorter working hours, the right to vote and an end to child

labor. They summed up their demands with the memorable phrase "Bread

and Roses" - they wanted both economic security and a better quality

of life. Both money and beauty, they believed, were necessary for a

sustainable life.

Three years later, a million women and men marched together in European

cities marking the first International Women's Day.

Today, as hundreds of thousands - if not, millions - of women all over the

world mark the 90'h anniversary of International Women's Day, we men are

also coming to realize that gender equality is in our interests as men,

that we will benefit from gender equality. That gender equality holds out

a promise of better relationships with our wives, with our children, and

with other men. Ninety-years ago, on the eve of the first International

Women's Day, an American writer wrote an essay called "Feminism for

Men." It's first line was this: "Feminism will make it possible

for the first time for men to be free."

Remember that phrase from the first Women's Day: Bread and Roses. Only

when we men share in the baking of the bread will we be able to smell the

roses.

----------------------------

* Michael Kimmel

Professor of Sociology

Editor, Men and Masculinities

Stony Brook

State University of New York

S406 Social and Behavioral Sciences

Stony Brok, NY 11794-4356

Tel: 1 516 632 7708

E.mail: mkimmel@notes.cc.sunysb.edu

http://www.sunysb.edu/sociology/faculty/Kimmel/index.html

Bibliography:

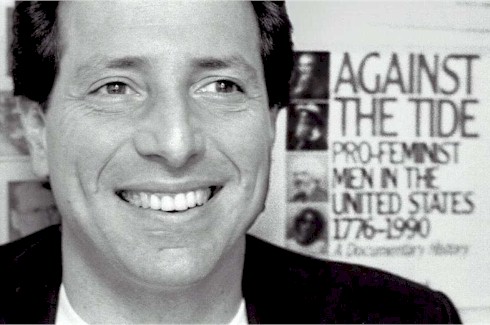

Michael S. Kimmel

is a sociologist and author who has received international recognition for

his work on men and masculinity. His books on masculinity include Changing

Men: New Directions in Research on Men and Masculinity (Sage, 1987) and

Men Confront Pornography (Crown, 1990), which was called “revelatory”

(Kirkus) and “timely and valuable” (Village Voice). His book, Against

the Tide: Pro-Feminist Men in the United States, 1776-1990 (Beacon, 1992),

is a documentary history of men who supported women’s equality since the

founding of the country. This “inspiring, pathbreaking collection of

remarkable documents” (Dissent) was also called “meticulously

researched” (Booklist) and a “pioneering volume” which “will serve

as an inspirational sourcebook for both women and men.” (Publishers’

Weekly).

His most recent book, Manhood

in America: A Cultural History (Free Press, 1996) was published to

significant acclaim. Reviewers

called the book “wide-ranging, level headed, human and deeply

interesting” (Kirkus), “superb… thorough, impressive and

fascinating” (Chicago Tribune), “perceptive and refreshing”

(Indianapolis Star). One reviewer wrote that “Kimmel’s humane,

pathbreaking study points the way toward a redefinition of manhood that

combines strength with nurturing, personal accountability, compassion and

egalitarianism” (Publishers’

Weekly). Another called it

“the most wide-ranging, clear-sighted, accessible book available on the

mixed fortunes of masculinity in the United States” (San Francisco

Chronicle). Another called it

“a cultural history as readable and fascinating as Kate Millet’s

epoch-making Sexual Politics (Booklist). The book also received impressive

reviews in The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post Book World (front

page review), and The New York Times Book Review, which noted that this

“concise, incisive” the book “elucidates the masculine ideals of the

past 200 years…just as shelves of feminist books have elucidated the

feminine.”

An edited book, The Politics

of Manhood (Temple University Press, 1996) develops a debate and dialogue

between pro-feminist men and the mythopoetic men’s movement, best known

through the work of Robert Bly. Bly

and Kimmel have recently begun a series of public debates and dialogues

about the politics of men’s movements.

Kimmel’s newest book, The Gendered Society will be published by

Oxford University Press in 2000.

Kimmel is also a well-known

educator concerning gender issues. His

innovative course, Sociology of Masculinity, is one of the few courses in

the nation that examines men’s lives from a pro-feminist perspective,

and has been featured in newspaper and magazine articles (The Wall Street

Journal, The Boston Globe, Newsweek, People) and television shows, such as

Donahue, Sonia Live, The Today Show, CNN, Smithsonian World, Bertice

Berry, and Crossfire. His

co-edited college textbook, Men’s Lives (5th edition, forthcoming) has

been adopted in virtually every course on men and masculinity in the

country.

His written work has

appeared in dozens of magazines, newspapers and scholarly journals,

including The New York Times Book Review, The Harvard Business Review, The

Nation, The Village Voice, The Washington Post, and Psychology Today,

where he was a Contributing Editor and columnist on male-female

relationships. He also is the

current editor of the international, interdisciplinary journal Men and

Masculinities. On the basis of his expertise, Kimmel served as an expert

witness for the U.S. Department of Justice in the VMI and Citadel cases.

Kimmel is National

Spokesperson for the National Organization for Men Against Sexism (NOMAS),

and has lectured at over 200 colleges and universities, and run workshops

for organizations and public sector organizations on preventing sexual

harassment and implementing gender equity, and for campus groups on date

and acquaintance rape, sexual assault, pornography, and the changing

relations between women and men.

BOOKS:

The Gendered Society. Oxford

University Press, forthcoming, 1999.

Manhood in America: A Cultural History. Free Press, 1996.

The Politics of Manhood. Temple University Press, 1995.

Against the Tide: Pro-Feminist Men in the U.S., 1776-1990, Beacon, 1992.

Men Confront Pornography. Crown, 1990; New American Library, 1991.

Men's Lives (with Michael Messner). Macmillan, 1989, 1992, 1995.

Changing Men: New Directions in the Study of Men and Masculinity, Sage,

1987.

Absolutism and its Discontents: State and Society in 17th Century France

and England. Transaction, 1988.

Revolution: A Sociological Perspective. Temple University Press, 1990.

ARTICLES:

“Integrating Men into the Curriculum” Duke J. of Gender Law and

Policy,1996.

"Does Censorship Make a Difference?: An Aggregate Empirical Analysis

of Pornography and Rape"

Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality.

"Masculinity as Homophobia: Fear, Shame and Silence in the

Construction of Gender

Identity" in Theorizing Masculinities, Sage Publications, 1994.

"Weekend Warriors: Robert Bly and the Politics of Male Retreat"

Feminist Issues, 1994.

"'Born to Run': Fantasies of Male Escape from Rip Van Winkle to

Robert Bly (or: The

Historical Rust on Iron John)" masculinities 1(3), Fall, 1993.

"The New Organization Man" Harvard Business Review, 1993.

"Consuming Manhood: The Feminization of American Culture and the

Recreation of the Male Body, 1832-1920" Michigan Quarterly Review,

Fall 1993.

"The 'Invisibility' of Masculinity in American Social Science"

Society, 1993.

"Men's Responses to Women's Demands for Educational Equality,

1840-1990" Thought and Action, 1992.

"Does Pornography Cause Rape?" Violence UpDate, June, 1993.

"Legal Issues for Men in the 1990s" University of Miami Law

Review,1992.

OTHER

PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITY:

Editor, Men and Masculinities (international, interdisciplinary

journal)

Editor, Men and Masculinities Book series, University of California Press

Editor, Sage Series on Men and Masculinities (research annuals)

Expert Witness for U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, in

Sex Discrimination Cases (The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute).

Men and Masculinities: Men and Masculinities was launched to publish high-quality, interdisciplinary research in the emerging field of men and masculinities studies. Men and Masculinities presents peer-reviewed empirical and theoretical scholarship grounded in the most current theoretical perspectives within gender studies, including feminism, queer theory and multiculturalism. Using diverse methodologies, Men and Masculinities's articles explore the evolving roles and perceptions of men across society. http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journals/details/j0244.html